“The Waiting Room” , a poem excerpt

“Every day, I try to see through the patient lens, and I ask: what can we do to change this broken system? To deliver healthcare in a way that treats people with the dignity they deserve? Will I do better tomorrow?”

This oncology clinician is passionate about patients being able to get the care they need. But every day he observes how social determinants of health, like access to housing, transportation or childcare, prevent this from being possible. “Is it ethical to start chemo for a patient who has no home to return to?” he contemplated. “Who was this system designed for?

As our conversation unfolded, I found myself more and more curious about why he cared so deeply about improving healthcare, so I inquired. “I’m Lebanese,” he began. “I grew up in Beirut during the civil war. People died in the streets every day and human life didn’t matter to those doing the killing. This is why I chose to go into the medical field.”

His openness brought me to tears. “When I reflect on what I see in healthcare today, I find myself wondering: how much better are we, really?” he said. “But everyone can do something small within the sphere of their control. Back home, my focus was education. Today, my focus is on each human being in front of me and remembering that we all have a story.”

The Waiting Room

Back home in Lebanon, the war was at its worst

in grades five, six, and seven

We slept inside the cold, cinder block stairwells

of a nearby building

Ten of us would fight for the spot

closest the candlelight

to finish our homework in the flickers

Staying focused kept us calm

‘cuz our teacher didn’t give a damn

why the math paper couldn’t get done

Before we’d leave for class each morning

mom would hug us in the kitchen, one-by-one

look you straight in the eyes, saying

what her words never would

(they knew killing a child

would send the strongest message)

Every day when I look in the mirror

I brush back my dark black curls

catch a quick glimpse of the scar

on the right side of my forehead

Many times as the snipers tried, this

was the closest they came

Having gotten good at dodging shots in the streets

hightailing, hill to hill, I’m among the lucky

Unlike too many patients I care for today

Most have to travel a long distance

only one bridge from there to here

four hours, on a good day

One patient, a single mom of three

has breast cancer

Couldn’t drop her kids to school

in time to make her appointment so

they sit with her in the waiting room

“Sorry, ma’am – we don’t allow children

and our policy clearly states

you’ll forfeit your appointment

if more than twenty minutes late”

The look in her eyes

no different from mom’s

those mornings in our Beirut kitchen

as she gazed her silent goodbyes

What is pain without a diagnosis? This is what occupied this patient before she even received her breast cancer diagnosis about a year ago. “I could feel the issue all the time,” she told me, and her concerns were confirmed when she finally did receive a diagnosis for her mysterious malady.

“I’m grateful to still be alive.” Her cancer diagnosis had given her a new perspective, allowing her to be gentler and more patient with life. She told me that she picked her battles more and was trying to be less of a people pleaser.

As a hospice doc, he thought about talking of death and dying. And then he thought about talking of the pandemic. He ended up talking about his son, who is now his daughter. Another part of his experience of continual growth and soul-opening.

She was a caregiver for the past two years of her husband, since his Stage IV cancer diagnosis, which she described as the hardest period of her life. This was significant as she had experienced much grief and loss in her life already, including the sudden death of her father, yet “grief with your partner sits heavier and harder.”

"I already had a mistrust of the healthcare system," he said. At first, he wanted to attempt to treat himself using home remedies. But he was led to innovative medical treatments by a caring Black female physician. "I'm about 85% now. I'll take that. It will be another year before I'm considered cancer-free."

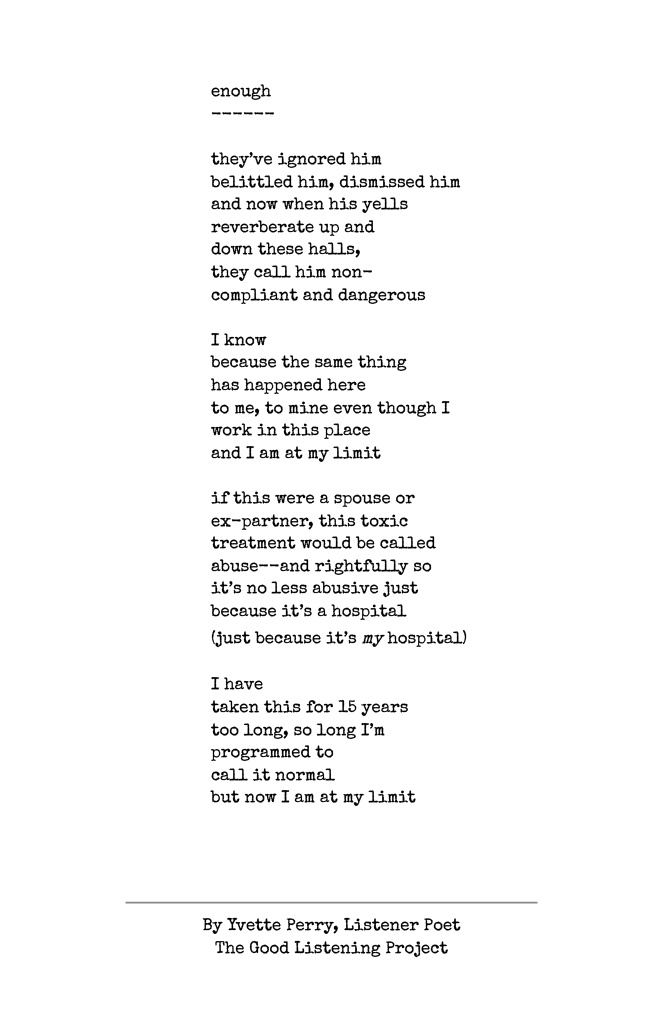

This nurse was considering leaving a position where she spent many years due to issues she experienced and witnessed at her hospital. Even though she worked there and was known to the healthcare providers, she experienced repeated incidents of disrespect and substandard care at the hands of her colleagues.

He noted that many of the people he worked with–mostly from communities underserved by the healthcare system–had to develop a new identity in the context of their caregiving responsibilities. "It's as if they need to become a new variant of themselves."

"What I've been thinking a lot about lately is hard to put into words," said this palliative care physician. At first she said this had to do with boundaries between herself as a physician and the patients and families she cared for–but she noted that this was perhaps not a precise enough word.

Throughout her 25 years with the American Cancer Society, her “why” has evolved. She believes that most of those who have connected with ACS began with a personal connection, but then, according to her, “you evolve, and you shift.”

With her background in counseling and psychology, she works to bring people together and support patients. When she and her husband lived in New Jersey, she answered an ad in a newspaper for the American Cancer Society. Her father-in-law’s struggle with leukemia made the work personal: “Maybe this is my calling.”

This poemee wanted to leave a legacy of doing good in this world. Although at times she becomes discouraged about the inequalities in the world, she is determined to do her part by making sure everyone has access to quality healthcare.

This person radiated gratitude and hope. She shared that she discovered she was expecting a son just before receiving a lung cancer diagnosis at the age of 31. Despite the challenges, she expressed profound gratitude for living in a human body and reflected on her transformative journey of self-discovery.

She had an epiphany as a child — that love could heal the world. Now, as a seasoned physician, there’s still a part of her that believes in the power of love, but not with the same idealism she once held.

This person is a neurologist of Romanian descent, in practice in the U.S. for 19 years, who draws inspiration from writers in his heritage. In his writing and work, he seeks to create a safe harbor for humanness while navigating the labyrinths of medicine to reach the essence of the humanity of his patients – even if all they want is a diagnosis or cure.

This poemee wanted to share her experience as a surgical resident, offering insight into the traditions that define this unique culture: the relentless pressure to succeed, the deference to those in higher positions, and the often-cold interactions that accompany a field-wide drive for speed and efficiency.

This new physician was looking forward to starting her OB/GYN residency. Her original goal in undergraduate school was physician assistant studies. But a series of experiences led her to consider a different path: medical school.

“I was at a birth recently and thought: This is why they are so afraid of us. They can’t control this” She sat on her couch with a mug of coffee. She is a queer, femme, mother of two who has worked in reproductive health for over two decades, first in abortion care and now as a doula for all, including queer and non-binary families, through the pregnancy spectrum. She has personally experienced birth, miscarriage, hysterectomy and surgical menopause.

A teenage cancer survivor, this poemee shared how she learned from the younger children she witnessed undergoing the same treatment she was. “You just see a difference in the way a child approaches it,” she said. “They have the moment, they have the pain, they have the shot, and then they just go back to playing. I always took strength from the way little kids would handle it.”

Conversation with Kimako Desvignes DNP, RN, Associate Director of Oncology with almost 30 years of experience in medicine, was an emotional journey through a history of social injustice and racial discrimination—a reflection on ancestry at times through shared tears. Henrietta Lacks’ story had a powerful impact on us both.

“Sometimes I feel so helpless,” said this resident, reflecting on all of the challenges faced by the young patients and their families whom she served. Over the last several days, she has become increasingly overwhelmed by events in the news and has questioned her ability to make a difference in the world.

“It’s hard to watch the decline and sometimes hard to visit but it weighs on me not to,” she said. Her father had always been an elaborate storyteller and an alive, vibrant man with a big voice.

The Good Listening Project was honored to once again take part in the annual KNN conference in Minneapolis this year. Jenny closed the session by writing this harvest poem that captured the voices and sentiments shared.

After a history of crippling endometriosis, this woman had an arduous, ongoing struggle with her healthcare community for the right to have a hysterectomy. She was finally granted approval at the age of 29. “It had been like pulling teeth, but finally I felt free,” she told me.

Her childhood was infused with Hawaiian-Polynesian music and dance, taught to her father by his mother. Today, her life’s work is to connect the unbelievable discoveries of molecularly focused pre-clinical research directly to the patient experience of treatment.

She is a single mother born to a single mother and had to grow up fast. She is juggling a sticky work situation, her own anxiety and depression, and being away from home and her kids.

Instead of the usual Listener Poet format – listening to one person’s story and responding with a framing narrative and custom poem – I was invited to create a group poem for forty participants at the Arts in Healing luncheon, hosted by the Inova Health Foundation in partnership with the board.

What does it mean for people living with Sickle Cell Disease to be seen, heard, and understood? For this person, it meant finding – and using – her voice to advocate for herself and for others.

“I’ve experienced a lot of big losses,” she said. “I want to be a beacon of hope and light, keeping the flame lit for cancer prevention.”

Professionally, for this person, Henrietta Lacks’ story represents the need to critically examine our research infrastructure. “Private companies benefit from publicly-funded research without a requirement to give back to ensure the viability of future research.”

“The fact of my life is a miracle,” she told me. Living with multiple chronic illnesses, this patient spoke to me of her journey with alopecia. Of how, in witnessing her body transformed by the condition, she continues to move at once through grief and reclamation.